Stridsvagn 74 prototype, 1957

Stridsvagn 74 prototype, 1957. Note the odd muzzle brake; as far as I know it was only used on this prototype (#701).

Stridsvagn m/39, Strängnäs, 1942

Stridsvagn m/39 from Södermanlands Regemente (I 10) on exercises near Strängnäs, August 1942.

Stridsvagn m/42 on an urban combat exercise, 1944

Stridsvagn m/42 on an urban combat exercise in the streets of Östermalm, Stockholm, April 29th, 1944.

Stridsvagn 103 0-series, Ravlunda, 1966

I’m sitting on a ton of photos from the national archives that aren’t of any use to anyone. That needs to change, so I’ll start posting one a day or so here. Enjoy!

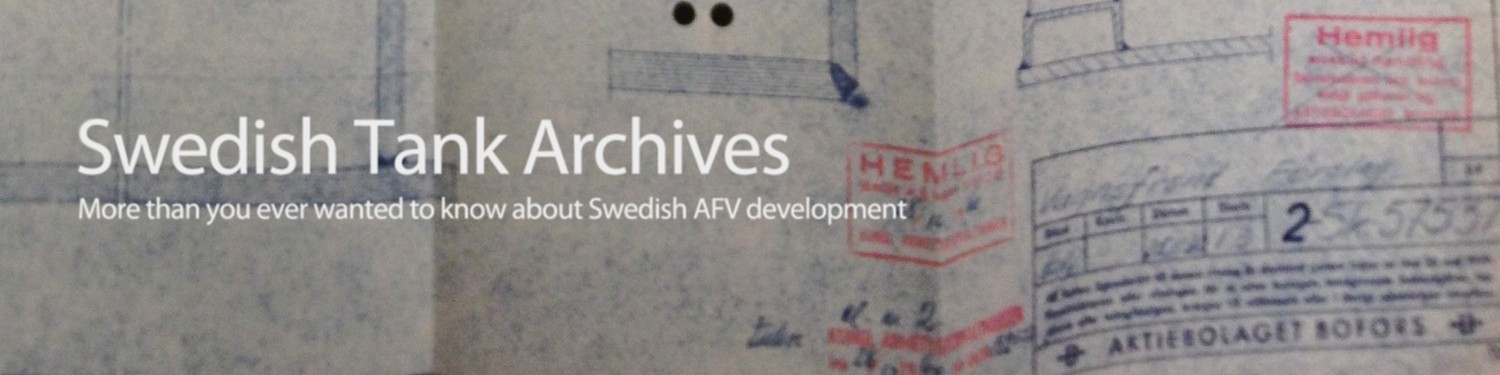

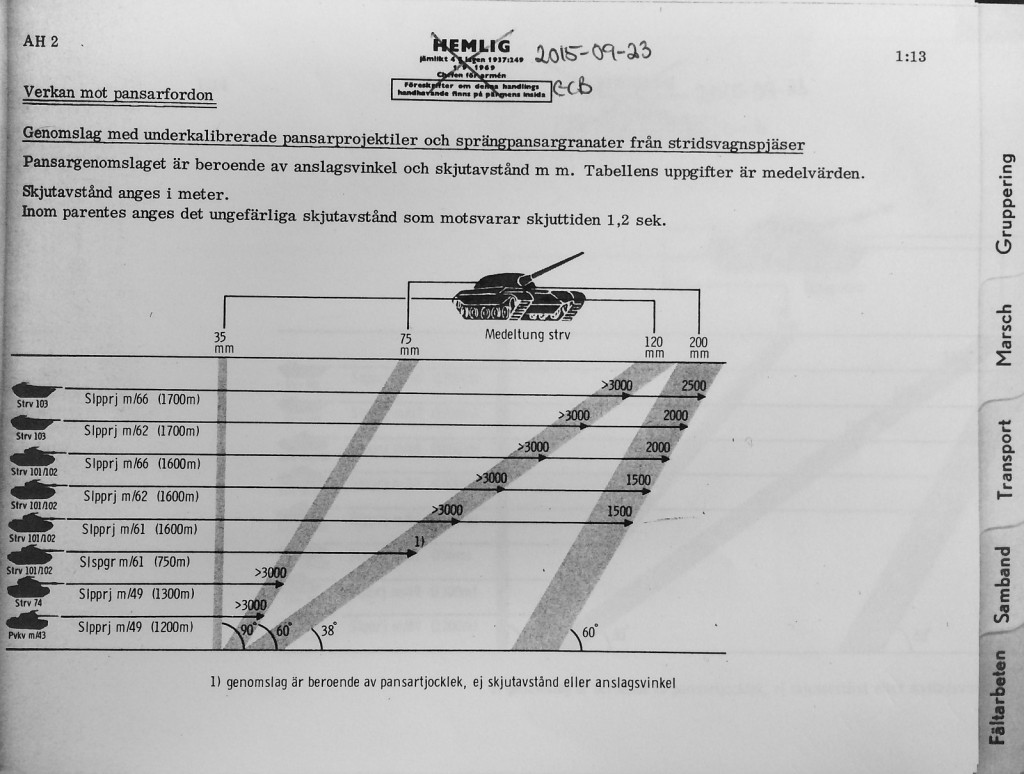

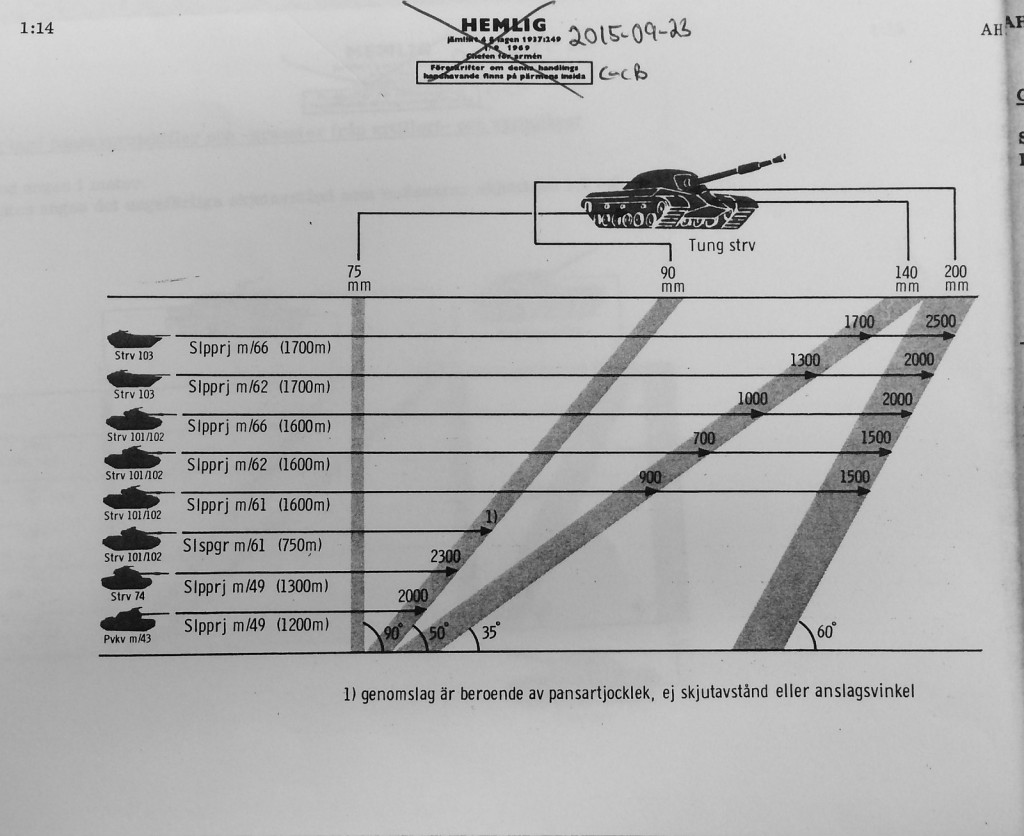

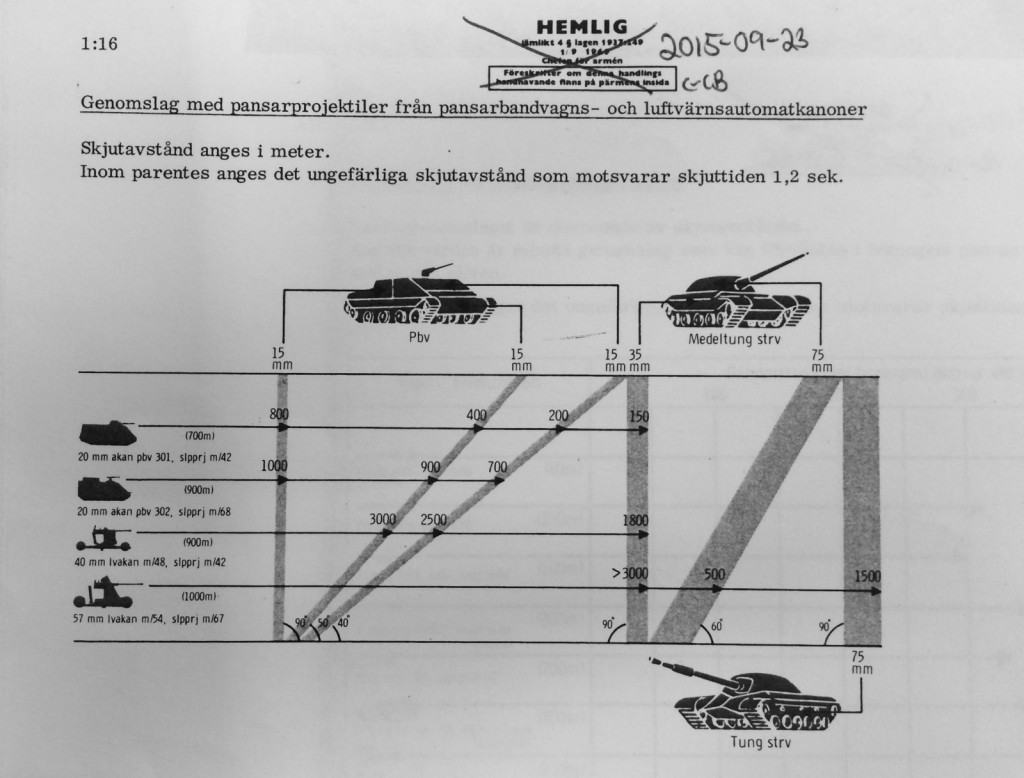

Armor penetration of Swedish tank and anti-tank weapons

After literally years of searching for an official Swedish penetration table of all anti-tank weapons in one place, a casual mention in the gunnery field manual finally set me on the right track. The official table is contained in a publication called “Arméhandbok del 2” (Army handbook or Army field manual, part 2), where I’ve never thought to look before. Part 1 contains tables of organization and equipment and is mostly unclassified, but part 2 is classified, is not listed in the national archives library catalog and does not have an unclassified table of contents – that’s why it took me so long to find it. The national archives copy is from 1970, so I got the relevant pages declassified without any problems.

The penetration figures are shown in the form of diagrams that show the typical maximum distance at which the given weapon and round can be expected to be effective against a fictive “threat tank” (most likely based on estimates of Soviet equipment), when hitting it in one of four places: hull front, turret front, hull side and turret side.

There are three such “threat tanks”. First, a medium tank (medeltung strv), which corresponds decently (but far from perfectly) to the real T-55A and T-62A, at least frontally. The real T-55A and T-62A have 100mm front plate sloped at 30° from the horizontal (not 120mm @ 38° – close enough, though), and the hull and turret sides are at least twice as thick in reality. Second, a heavy tank (tung strv), which is probably intended to represent the T-10 – I don’t think it matches very well, though. Lastly, an APC (pbv), which just has 15 mm of armor all around.

For all diagrams except the HEAT one the grey bars in the diagram symbolize the armor plates on different parts of the enemy tank, their slope and relative thickness. At the bottom of the diagram, next to each “armor plate”, the angle from the horizontal plane for that plate is given, so the impact angle from the geometric normal of the plate is the complementary angle (90 minus the given angle) to the given one. At the top of the diagram is the thickness of the armor plate, and a guiding line that shows where on the tank it’s located. From left to right, the armor plates shown are: hull side, turret side, hull front, turret front.

The leftmost column show the firing tank, the round used, and (in parentheses) the the typical distance equivalent to a round flight time of 1.2 seconds. The arrows extending from the gun show the maximum distance (in meters) at which the given armor plate can be penetrated with the given gun and round.

These two diagrams show the performance of tank (and TD) guns. Strv 101/102 is the Centurion with the 10,5 cm L7 gun; the Strv 103 has the same gun but with a longer barrel. Both Strv 74 and Pvkv m/43 both have 7,5 cm Bofors guns that can fire the same rounds, but the latter’s gun is slightly shorter.

The rounds used are:

- Slpprj m/66: Swedish designation for the British L52A1 APDS. 61 mm penetrator.

- Slpprj m/61: Swedish designation for the British L28 APDS. 60 mm penetrator.

- Slpprj m/62: a Swedish-developed APDS round. 57 mm penetrator. Mainly intended to secure a domestic supply of ammunition and with the hope of getting a round superior to the British one. After developing it, the army got into an argument with the Brits about licensing fees and patents for it (the Brits claimed it was based on their design).

- Slspgr m/61: a British HESH round. The footnote says “penetration does not depend on range or angle”. This round was rarely used in Sweden; the army thought it was prohibitively expensive compared to regular HE rounds.

- Slpprj m/49: a Swedish APDS round.

This diagram shows the performance of AP and APHE rounds fired from howitzers, antiquated AA guns and old WW2 tank guns now mounted in fixed fortifications. From top to bottom, the guns listed are:

- 10,5 cm haub m/40: a Bofors-made howitzer, firing a WW2 vintage APHE round.

- 7,5 cm kan m/41 strv: the gun for the Strv m/42, firing its original WW2 AP round. By this time, this gun was only in service as a fixed fortification.

- 7,5 cm lvkan m/30-37: a Bofors AA gun, firing a WW2 AP round.

- 57 mm pvkan m/43: a Bofors towed AT gun, firing a WW2 APHE round.

- 37 mm kan m/38 strv: the gun used on all the Swedish WW2 light tanks, such as the strv m/38, m/39, m/40 and m/41, firing a WW2 APHE round.

This diagram shows the performance of various autocannons firing AP rounds. The guns are:

- 20 mm akan pbv 301: a 20 mm Bofors autocannon, firing a WW2 AP round. The gun was surplus, taken from decommissioned Saab 21 strike aircraft.

- 20 mm akan pbv 302: a 20 mm Hispano-Suiza autocannon, originally mounted on the Saab 29 Tunnan aircraft.

- 40 mm lvakan m/48: the famous 40 mm Bofors gun, L/70, firing a WW2 AP round.

- 57 mm lvakan m/54: a Bofors 57 mm AA autocannon, big brother to the 40 mm L/70. Did not last very long and was retired long before the 40mm.

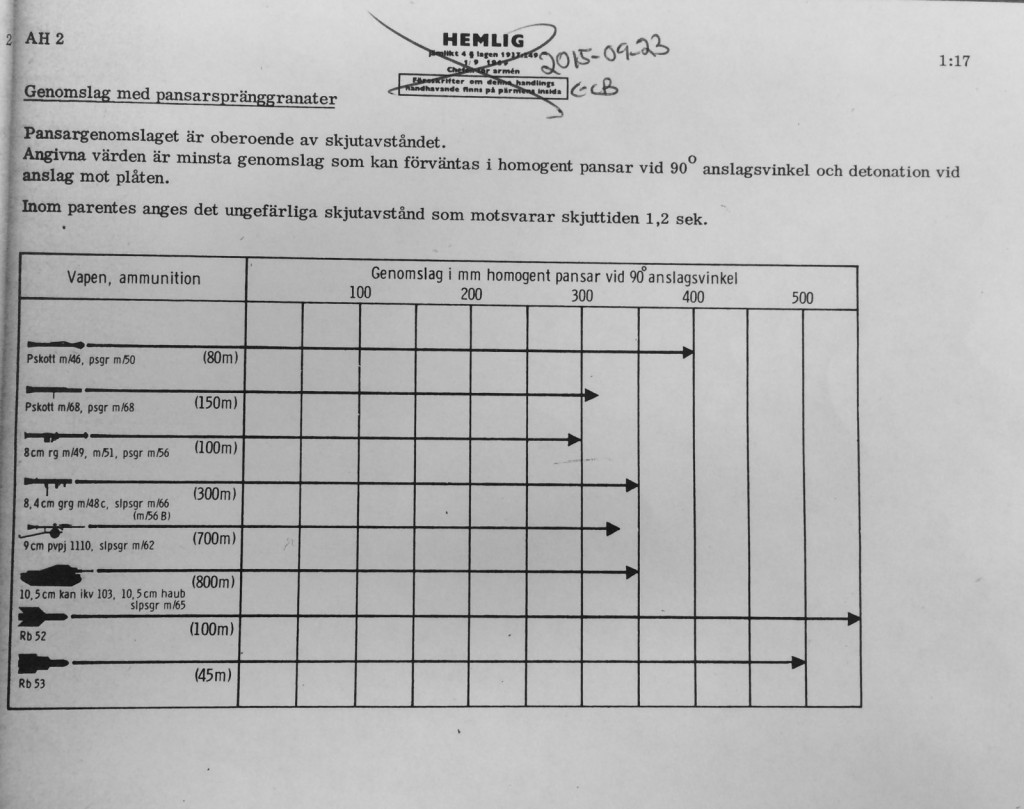

This diagram shows the performance of various HEAT rounds. Unlike in the previous diagrams, this one simply shows the penetration in mm (scale in the upper part of the diagram) against a vertical plate of homogeneous steel armor. The weapons are:

- Pskott m/46: a Swedish copy of the Panzerfaust, but with a new warhead.

- Pskott m/68: also known as the Miniman; a disposable recoilless launcher.

- 8 cm rg m/49 and 8 cm rg m/51: a multi-use RPG-like recoilless rifle, firing a mid-50’s HEAT round. Rg stands for raketgevär.

- 8,4 cm grg m/48: the famous Carl Gustav recoilless rifle, firing a mid-60’s HEAT round.

- 9 cm pvpj 1110: a 9 cm recoilless rifle with a very long barrel, firing an early 60’s HEAT round. Commonly found towed or mounted to a Volvo jeep, but could also be pulled on a sled behind a skiing troop.

- 10,5 cm kan ikv 103: the gun on the ikv 103, firing a mid-60’s HEAT round. Also included here are various 10,5 cm howitzers that could fire the same round.

- Rb 52: the Swedish designation for the French SS-11 ATGM.

- Rb 53: a Bofors-designed ATGM, also known as Bantam.

A tale of Swedish military procurement

Or: how we ended up with the stridsvagn m/42.

In 1930’s Sweden, there was an engineering and machinery firm named Landsverk. Founded in 1872, it was originally a manufacturer of steam engines, agricultural machinery, railroad cars and other such things. The company was bought up by new German owners in the mid-1920’s after a period of economic troubles, and suddenly around 1930 it sprouted a new armored vehicles division under a Dr. Ing. Otto Merker (he left the company in 1936, went back to Germany and had a quite successful career in the Nazi Reichsministerium für Bewaffnung und Munition where he later worked on the type XXI submarines, but that’s an entirely different story).

Either way, around 1936-1938 Landsverk developed a new light tank design called L-60. It was a cute little thing of about nine metric tons with a three-man crew, armed with a 37mm Bofors AT gun or a 20mm autocannon. Very modern for its time, it featured torsion bar suspension, a fully welded hull and elegantly sloped armor. The Swedish army, originally interested buying upwards of a hundred, ended up with having enough money to buy 16 (sixteen), designated stridsvagn m/38 (tank, model 1938), and then another 20 in 1939 with some improvements (the improved model appropriately designated stridsvagn m/39).

Then war breaks out, Norway and Denmark gets invaded by Nazis, Finland is hanging on for dear life against the Russians, the situation is about as awful as it can get without outright war, and suddenly there’s money to order another 100 or so, this time with three times as much front armor. In fact, there’s money for a lot more than that, but there’s a production capacity bottleneck. Still, about at this time people start to realize that regardless of how modern the L-60 design is, literally everyone else is building tanks that weigh at least three times as much and are armed with guns of at least twice the caliber. Steps have to be taken, and after much hemming and hawing, in 1941 an “armor committee” is appointed and tasked with developing a new “heavy” tank. Only, not that heavy, because the design goal is 20 tonnes and there’s a strict weight limit of 21 tonnes (then later grudgingly raised to 22 tonnes). Sweden in the early 1940’s is not a very car-reliant society and a heavier tank would have far too many problems with strategic mobility since – among other things – it wouldn’t be able to cross most bridges.

When the armor committe finally gets the ball rolling in spring-summer 1941 there’s no time to develop a new design from scratch and there are no foreign designs that are both good enough and possible to license, so Landsverk dusts off a 16-ton design called Lago, developed around 1938-1940 and originally intended for export to Hungary (which also built the L-60 on license – locally called the Toldi). The chassis is stretched (too much, as it turns out – the tank ended up hard to steer because it was too long in relation to its width) and the armor improved. The army really wants at least 60 mm of frontal armor, but can’t get it within the given weight limits and has to settle for 55 mm.

A new turret is developed and gun choices are debated. The army primarily considers three alternatives; a relatively long 57mm gun (good against armored targets), a very short 10,5 cm howitzer (good for lobbing big blobs of HE) and a medium-short 7,5 cm gun that’s somewhere in between. In the end the army goes with the 7,5 cm, and – in order to avoid re-tooling factories and retain ammo commonality with the light field artillery – chooses an existing shell casing with a rather limited space for gun powder. As a result of that and the short barrel the muzzle velocity is rather low and the gun ends up being quite similar to the one on the 75mm Sherman. The design goal is to be able to penetrate the most modern foreign medium tanks in the side at distances up to about 800 meters – penetrating them frontally would require a much longer and heavier gun (similar to the 7,5 cm AA guns available at the time) that would go far over the weight limit, so that role is left to a future dedicated TD design.

The tank is to have two engines – a pair of Scania-Vabis’ tried and trusted L603 design, which was also used on the L-60. The gearbox is an issue, though – there’s no existing gearbox design available in the country that is both compatible with a twin engine arrangement and is suited for a vehicle this heavy. The Atlas-Diesel company (today better known as Atlas Copco) offers to develop a new hydraulic gearbox, but it’ll take too long to get ready and it’s rather heavy and bulky, too, in a tank where every kilogram is precious. In the Lago prototype, Landsverk had used a gearbox manufactured by German engineering firm Zahnradfabrik Friedrichshafen, so the army contacts them about buying it for series production. The company happily offers what they call the gearbox of the future, an electromagnetic design originally designed for trams or rail buses, which promises to be both efficient, very light and small and easy to use, but best of all it can be delivered immediately. The sales engineers make all kinds of exciting claims – this gearbox will be used on all new tanks in 3-4 years from now, a bigger version is used on the famous Tiger tank and the magnetic plates that control which gear is used are said to last basically forever. They can’t leave any guarantees that specify that the gearbox will work for a fixed number of kilometers, but they’re absolutely convinced the army will be satisfied. (If this sounds like a scam, that’s because it is – basically none of the claims turned out to be true.) The army is still somewhat suspicious of this new and untried technology and as a precaution orders two sets of gearboxes for every tank; one electromagnetic from ZF and one hydraulic from Atlas-Diesel. A hundred tanks are built with the electromagnetic gearbox since that’s what available immediately.

When it comes to manufacturing these tanks, Landsverk alone does not have the production capacity to do it (and it would be very unwise to concentrate all tank manufacturing to a single place, especially one as close to the continent as Landskrona). A hundred are ordered at Landsverk, and additionally the army contacts Volvo in order to negotiate a contract for license production of another sixty. Instead of accepting this lucrative business in troubled times, Volvo makes a huge fuss about its civilian market share. The tank has an engine made by their greatest competitor on the civilian market; building a tank and fitting it with the competitor’s engines is simply unacceptable. “How”, cries Volvo’s CEO, “could we look our retailers in the eye if they ask us why – when it really mattered – the army chose our competitor?” Volvo doesn’t have any suitable engine ready though, and would rather not take the contract at all, not even at an inflated price. Since there aren’t exactly a lot of manufacturers available, the army basically threatens to place the company under direct government control for the duration of the war. Volvo makes a counter-offer and says they’ll build 55 tanks with the Scania-Vabis engines, but for the last five they’ll develop a new engine of their own. The army grudgingly accepts this and in the end, after many teething problems and even more gearbox problems (adapting to the new engine is not entirely unproblematic), a total of 57 tanks out of 282 total built are fitted with a single Volvo engine instead of two Scania-Vabis ones. The Volvo engine is more powerful but also turns out to be considerably less reliable.

For no real good reason, the tank now exists in three different versions with completely different drive trains: strv m/42 TM, TH and EH. TM means two engines and electromagnetic gearbox, TH means two engines and hydraulic gearbox, and EH means for one engine and hydraulic gearbox.

When the first version – the TM – gets out into the field, it’s a disaster. The electromagnetic gearbox is more efficient and provides more power at the drive wheel than the hydraulic one does in most situations, but it is catastrophically unreliable. In October 1944, the 3rd Armored Regiment at Strängnäs reports that 51 out of 89 strv m/42’s with the ZF gearbox are unserviceable, largely because of problems with the gearbox. The magnetic plates (said to be “eternal”) break all the time, sometimes after only tens of kilometers, and when sent for analysis at a lab at Svenska Kullagerfabriken (SKF) it turns out ZF has cut some rather important corners and the steel is of very poor quality, full of dross. The entire thing frequently overheats. The government appoints an investigative commission which asks a lot of involved parties some very pointed questions, and sabotage by prisoners of war at ZF’s factory is discussed as a possible theory. In the end it takes several years to sort out these problems (plates redesigned several times and new ones manufactured in Sweden under extremely strict quality control at Sandvik AB, lubrication adjusted several times etc).

The army gets sick of this and when developing the new pvkv m/43 tank destroyer on the same chassis also orders yet another gearbox design, this time from Volvo. Studying captured T-34’s in Finland has proven that an entirely mechanical gearbox for a tank in the 25-30 ton class with very powerful engine is definitely possible, and the Russians seem to know what they’re doing, so the new gearbox is entirely mechanical. After the war, all strv m/42 TM’s are refitted with new gearboxes: 30 get Atlas-Diesel’s hydraulic one (becoming m/42 TM) and 70 get Volvo’s new mechanical one and a new designation, strv m/42 TV (two engines, Volvo gearbox).

Meanwhile, already in 1943 it’s becoming apparent that perhaps that short 7,5 cm gun wasn’t sufficiently powerful after all, and the army starts looking at alternatives. Like in many other countries the obvious choice is an anti-aircraft gun, more specifically a Bofors pre-war 7,5 cm design that heavily inspired the German 88. It is tested on the tank in a new turret in 1945 but technical problems and the end of the war make the entire thing come to nothing. Instead, the tank soldiers on into the late 50’s, when it finally gets a new turret and the old AA gun for real, becoming the strv 74. The Volvo-engined tanks are not upgraded and are instead kicked out of the tank brigades and into an infantry support role. The strv 74 serves in tank brigades until the late 60’s, by then thoroughly obsolete as a frontline tank, and is then kicked into the infantry support role and replaced by the strv 103. The last strv 74’s then serve in reserve infantry formations until the early 80’s, ending a very long career for a quick wartime improvisation of a tank.

Ballistic tests with HEAT rounds against chain armor

A test report from 1971, documenting test firings with two different HEAT rounds against a stand-off “armor” screen made out of steel chains. The target looked like this:

From left to right, chain links, one meter of air, 110 mm armor plate, then eight layers of 25 mm “commercial iron” plates (probably equivalent to mild steel). The chain links were 113 mm long and 62 mm wide with a diameter of 19 mm. The chains were spaced at 100 mm intervals.

A summary of the report states that on average, for 9 cm HEAT rounds (pansarvärnspjäs 1110), the penetration was about 40% of what it should be at the same standoff distance, while for 8,4 cm HEAT rounds (8,4 cm granatgevär m/48, aka “Carl Gustav”) the penetration was about 75% of the expected.

A translation of the results follows below; for images see read the PDF version (in Swedish).

Archive reference: SE/KrA/0092/A/A2/001:H/F1-1971/50

Leichttraktor manual

Recently at the national archives, I was poking around a few huge boxes of unsorted tank and armored car photographs from the 1920’s and 1930’s and made an unexpected discovery. In one of the boxes was a folder with sales photos for various foreign tanks from the late 20’s/early 30’s (Renault NC 27, Fiat 3000 and one or two others), and at the back of the folder was a complete instruction manual (in German) for the Leichttraktor, including a number of photographs of both exterior and interior.

The Swedish army was shopping around for new tanks around 1930, and while they ended up with the Landsverk L-10 and L-30 (strv m/31 and strv fm/31), one of the offers that was considered was for Bofors to license build the Leichttraktor, and that’s most likely the reason why the manual ended up in the Swedish archives.

You can read the manual in PDF form here. At the very end is a few instruction booklets for various sub-parts (fuel distribution system, brakes etc). I’ve only photographed the covers of those; let me know if you desperately need them.