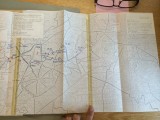

Report from British strv 103 trials at BAOR, 1973

In the summer of 1973, the British Army on the Rhine (BAOR) evaluated the strv 103B in the field. The crews were ordinary British tank crews from the 2nd Royal Tank Regiment, who were sent to Sweden to train on the 103 for four weeks. Ten tanks were then sent to Germany for several months worth of field trials. This report, authored by the Swedish observers from the Swedish Armored Forces School covers the results – such as they were – of these trials.

In general, the observers consider the results of the evaluation to be highly dubious at best. The trials were conducted in such a haphazard and unscientific manner that the results were considered mostly useless. The observers also devote a lot of space to scathing criticism of the BAOR. I’ve translated some of the more interesting passages below – it’s highly entertaining reader.

By request from a reader, I have provided the report as a PDF in addition to the ordinary image gallery.

The observers on the quality of British tank gunners

At the end of the gunnery training, there were two tests with a gun camera, one against a fixed target and one against a moving one, as per usual Swedish standard. The results were bad. The first time these results may possibly be explained by the gunners not taking the trial seriously, but even after they had evaluated their own results and re-did the test the results were very bad. It is possible that more training could have improved the results somewhat, but the more likely explanation is that a large portion of the British gunners simply weren’t suited to their job as gunners. In some cases, problems with bad eyesight were apparent. It should be noted that British tank personnel is not tested in the same way as Swedish personnel before being assigned as tank gunners.

(pg 15)

Both the methods the tank crews used for engaging targets and their aiming skills were unacceptable and clearly worse than that of the average Swedish crew.

(pg 15)

Swedish tank crews were conscripted. Tank crews were considered a particularly demanding position and the requirements for getting assigned to one were very high.

On crew resource management etc

The number of targets detected was on par with the performance of Swedish crews. However, the time from detection to opening fire was in most cases far longer than can reasonably be expected. In part, this is due to lack of training on the 103, but more importantly it’s also due to the way the British crews work together. The tank commander always have to give orders about everything and the gunner is forbidden from opening fire on his own initiative when he spots a target, unlike in Swedish regulations for tank crews. Just like in the 1968 trials, it has been impossible to convince the Brits to try the Swedish method, which is also employed by the Germans for example. The reason cited by the Brits is that tanks carry so few rounds that the commander cannot risk the gunner opening fire on a non-essential target and that the gunners in general aren’t all that good at neither judging the importance of a target nor at correcting their own fire.

(pg 14)

Nor were the Brits willing to accept the principle that whoever sees a target first fires on it. If the tank commander spots a target, the gunner should still open fire on it. According to Swedish tests, if the commander has to hand the target over to the gunner, the time to open fire is on average two seconds longer than if the gunner opens fire by himself. If questions regarding the target’s exact position are raised, this time increases further, up to 10 seconds or more in many cases. Our proposal to try the Swedish method in parallel with the British was rejected without any reason given.

(pg 14, pg 45)

These limitations in engagement methods severely limited the advantages of the strv 103’s duplicated controls.

On discipline and exercise of command

Exercise of command was relatively tame and commanders rarely supervised anything. The subordinates were left with a lot of freedom to complete rather ill-defined tasks on their own. When it came to looking after their equipment, the personnel was rather sloppy and nonchalant.

(pg 13)

On tactics

(in a discussion on fighting delaying actions) The target marker equipment made this exercise an excellent and very illustrative example of how not to fight this type of action (in both Chieftain and the strv 103).

(pg 85)

We would like to call some attention to the British regulations on deployment width for tank platoons. When deploying for defense, a platoon can be deployed over a width as great as 800 meters! Even during attacks, the width frequently reached 5-600 m. The combat simulation equipment often proved that these regulations are clearly inappropriate. The platoon rarely had any means of concentrating its fire and thus the enemy picked tanks off one by one. The British reasoning is “the enemy advances on a broad front and has many tanks, we are few but must cover the entire width”. The German liaison was horrified by this philosophy and the British conduct!

(pg 45-46)

On performance in major field exercises

The last part of the trials was conducted as a major field exercise. The BLUFOR had Chieftains only, the OPFOR mixed Chieftains and strv 103’s. The OPFOR “won”, but the Swedish observers dismiss the results as “highly questionable”.

The BLUFOR tank units appear very unprofessional. They use unsuitable formations, roads and combat positions. In general, they appear to think they are invulnerable. Tank commanders and loaders stand very far up in their hatches. Drivers have hatches open and drive with their head above the edge.

There is no coordination of attacks between tanks, infantry and artillery. Tanks attack alone into forests. Infantry attacks alone across open fields straight at defending tanks. When attacking, units are not concentrated, neither in space nor in time. Attacks are always conducted in a “trickling” fashion.

Radio traffic is very intensive but there are rarely orders given.

At the OPFOR, unit commanders are often deployed very far behind their units, battle group commanders about 5 km behind and combat team commanders 500-1000 meters behind.

CYCLOPS (the strv 103 squadron) combat positioning during the delaying action was usually pretty good.

All tanks, both Chieftain and strv 103’s, are driven very carelessly. No attention is paid to neither civilian traffic nor property damage. Reports on engine failures have a hard time reaching the maintenance units. Map reading capabilities are overall very bad.

When the exercises ends, 9 out of 10 strv 103’s are fully combat ready.

The experiences from these exercises appear to be highly questionable.

(pg 141-142)

British tank crews always carry a lot of baggage, both combat and non-combat equipment (cooking equipment, food, tents etc), on and/or in their tanks. Unlike our crews, they are completely independent of separate cooking units and baggage trains. This meant that the space available in the strv 103 was far too small for their equipment.

(…)

Very little attention is paid to the fact that the unit is exercising on private property. Driving on public roads is very careless and the exercise area is not marked or delimited. Damage to planted fields is frequent despite good opportunities to choose routes over fields where the harvest has already been taken in. Apparently the property damage costs for a similar exercise in the same area last year were on the order of 10 million SEK (about 62 million SEK today, ~6 million EUR). These damages are paid for by the German authorities. During this year’s exercises, five people died in accidents; during the same exercise last year, thirteen people died.

Strike aircraft are available on request during the exercises. Helicopters are used for both recon and command duties. The routines for coordinating with airplanes and helicopters seem to be well developed. The British command APC is well suited to its purpose and the space available is better than in our equivalent vehicle. Wired communications are not used between brigade staffs and battle groups. The system with call signs painted on the rear of the tanks appears to work well.

(…)

Deployment width and depth is considerable in the smaller units. Tank platoons are often deployed over a width/depth of 600-800 meters. (…) Tank platoons are frequently deployed independently behind each other. Support is organized within the platoon and not between platoons. The rear platoon is usually 500-1000 meters behind the front one. Hence, the result is that the enemy knocks them out one by one, platoon after platoon. Both platoon commanders and tank commanders act very independently and choose both their own routes and positions and their own timings for advancing or repositioning. The whole thing frequently resembles a guerrilla war or every man for himself.

The infantry is used way too late to take terrain from which the enemy can fight the tanks up close with weapons such as recoilless rifles. The tanks attack first. When they start taking fire, the mechanized infantry is deployed. There is no planning for attacks in depth. On the first day, it took seven hours to advance seven kilometers with the BLUFOR’s combat team (17 tanks and a mechanized infantry platoon) against an OPFOR with 9 tanks and one mechanized infantry platoon, deployed in three lines.

If a platoon or squadron commander’s tank gets engine problems, the commanders do not move to another tank. Tanks are frequently deployed in very unsuitable positions where they are easily knocked out. The observation and recon duties are conducted badly. The soldiers seem very passive. Chieftains are often positioned behind a ridge with the gun and the chassis side against the enemy. The strv 103 crews rarely clean their optics.

When fighting a delaying action, the tanks in a platoon retreat by turns along the whole depth of the deployment. Withdrawal is frequently started far too late, and the tanks are thus knocked out one by one. Despite the terrain allowing opening fire at long distances (2-3 km), fire is often opened far too late (500 m). There is never a rear platoon deployed to cover the front platoon’s withdrawal.

In light of the heavy criticism above, it has been very hard to judge how well the strv 103 has proven itself. The results have mostly been influenced by troop performance and not by the tank’s performance. As far as it has been possible for us to observe, though, we cannot say that the strv 103’s have suffered more losses than the Chieftains.

Strv 103 availability has been good. Most of the time all tanks have been in working condition during the day. On the OPFOR side, the Chieftain availability has dropped steadily. Near the end of the exercise the availability was down to 50%, and thus a Chieftain platoon was transferred from BLUFOR to OPFOR.

(pg 127-128)

On British vehicles

The Chieftain tank:

The reliability seems surprisingly low. During the exercises, the number of tanks that had to drop out due to mechanical trouble was relatively high. Mostly, it’s the engine that is the problem. When a Chieftain stops, after a little while there’s always an oil slick on the ground or garage floor under it. The gun stabilization also fails frequently. The accuracy of the contra-rotating feature in the commander’s observation cupola is very low. It is almost never used by the Brits. The tank’s speed over terrain does not seem to be superior to that of the S-tank. The commander’s observation equipment is very good.The Scorpion tank:

The Swedish personnel got an excellent briefing on the tank and was also allowed to drive it. It is very fast and easy to drive. The observation equipment is absolutely excellent. (…)The FV 432 APC:

Appears to have a large number of different reliability problems, mainly concerning the steering gears. The vehicles are so far gone that they are considered a danger to traffic. According to maintenance personnel, a lot of the problems are caused by the soldiers not doing sufficient daily maintenance.(pg 146)

Read the entire report in PDF form, or hit “Continue reading” to browse the photographed document images on this web page.

Archive reference: SE/KrA/0092/A/A2/001:H/F1-1974/35

[…] Swedish Tank Archives has posted an interesting piece concerning a report from British Strv 103 (S-tank) trails from 1973. In the Summer of that year the British Army on the Rhine (BAOR) sent several tank crews to Sweden to train on the S-tank for four weeks. These crews were then sent to Germany along with the S-tanks to be tested. The Swedish observers of the test considered the results of the evaluation to be highly dubious, claiming that they were conducted in a haphazard and unscientific manner. They also are quite harsh in their criticism of the BAOR. […]

I rather suspect that the Swedes are full of it- OR the British Tank Crews have forgotten all they ever learned

what nonsense – not doing daily maintenance- any Tank would fall apart if that were so

Cheers

[…] You can view some translated sections of the Swedish report and some fascinating photographs of the exercise by clicking here […]

Sir

In 1973, I was attached to 2RTR in Muenster, West Germany, during the period when CYCLOPS returned from Sweden with 10 Strv 103B S Tanks, accompanied by a number of Technicians and Volvo truck from the Swedish Armour School. I must say they looked very smart in their pristine green coveralls, had an enormous array of tools that the average REME VM could only dream of, but appeared to be appalled to get their hands dirty, in the same way that was a regular feature of “A” Vehicle Mechanics in the Squadron Fitter Sections. I know, because I had previously spent time in the CYCLOPS Fitter Section and knew the crews and fitters particularly well.

I am somewhat disappointed by the criticism of those personnel in the report posted. They failed to take into account the tactics employed on the North German Plain over which much of the battle was expected to take place during the Cold War. The S Tank, whilst mechanically proficient, was not designed to fight in the West, but would be deployed to the forests of Sweden where the emphasis on manouevre and fire control was less important.

To be fair to the skill of the crews chosen to man the S Tank during the trials, each Troop lost one man from each crew because the S Tank only required 3. British crews were trained to work as a team, unlike the Swedes, who were expected to multi-task and work individually, therefore I believe the criticism made was totally unfounded and ill-judged.

Hi there,

what a cracking report here to read! I’m one of the webmaster of http://www.military-database.de, so a while ago I got some great snaps from a soldiers who was attached to 31 Armd Engr Squadron. He took part in the same exercise “Eye Shadow” but he can’t remember the name of the Ex. So just found your report and photos today, specially the photos around the Kassel area!! And so I’m able to close a part of our website! I know there was an Exercise where the British government tested the STRV. But I don’t know before that was “Eye Shadow”. Really glad to found your blog!

So I would like to ask, if there is a chance to use the photos of the report here on our website! Would be great if there is a way!

Best regards Arnd

haha ebin

BAOR was a rather dispirited and useless bunch of uneducated football hooligans only interested in getting drunk on cheap german beer and into bar fights with the lnatives over the local girls.

Stuck-up and bone-headed officers with an elitist attitude from colonial times.

‘In three days to the Rhine’ was possible.